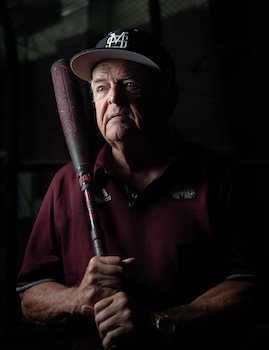

The father of SEC baseball

Ron Polk laid foundation for Mississippi State’s national championship baseball program

In explaining the natural world, Aristotle introduced the idea of first cause, which maintains that things in nature are caused by a chain of events stretching back in time. What is now owes its existence to something that came before.

The argument has been debated throughout the centuries, most often in philosophy and theology.

Yet the first cause has also been applied to explain other things.

Even baseball.

On the evening of July 2, two days after Mississippi State captured its first national championship with a win over Vanderbilt in the finals of the College World Series, an estimated capacity crowd of 15,000 fans flocked to MSU’s Polk-Dement Stadium/Dudy Noble Field to celebrate, roaring with applause as the players, both past and present, coaches and athletic department officials were introduced. Some were greeted with standing ovations, including coach Chris Lemonis, who delivered a long-awaited national championship in just his second full season in Starkville.

Ron Polk, 77, was not at the ballpark that night. As he has been for close to a decade now, he was coaching baseball in the Cape Cod League. Yet when Polk’s name was announced at the ballpark, MSU fans stood as one, a standing ovation in absentia.

Bulldog fans know a first cause when they see one.

In truth, Mississippi’s journey to the 2021 National Championship did not begin when the season started, nor even with Lemonis’ arrival in Starkville.

It began 45 years earlier, when Polk took the MSU coaching job. For 29 years, in two separate stints as the Bulldogs’ coach, Polk not only built the Bulldogs into a national contender (he led MSU to six of its 12 trips to the CWS and 20 NCAA Regional appearances with just one losing season), but transformed SEC from a conference whose success in baseball was best described as sporadic into the dominant baseball conference in the nation, earning the title “Father of SEC Baseball.”

“Some would say Godfather,” Polk says when asked about the title, a sly allusion to his advocacy for conference rules changes needed to make the SEC competitive and his long-running — and to date, unsuccessful — fight with the NCAA over baseball scholarship limits.

“I was the bad guy with the NCAA, the guy who gave all the other coaches cover. Everybody knew the scholarship limits were ridiculous. I was just the guy who said it out loud,” Polk says.

The road to MSU

If Polk is a first cause for MSU baseball, he has a couple of first causes of his own — his mom’s respiratory illness and Ron Fraser’s decision not to take a job with the Chicago White Sox.

Polk was born in Massachusetts, then lived in Buffalo, New York, before his mother’s respiratory problems led the family to move to Phoenix, Arizona, where the dry air was considered helpful for those with breathing issues.

“If we don’t move to Phoenix, maybe none of this happens,” Polk says.

It was in Phoenix that he fell in love with baseball. Polk was a middle infielder at Grand Canyon College, a small Southern Baptist college located in southwest Phoenix. After graduation, Polk spent a year as a graduate assistant at Arizona and another year as an assistant at New Mexico before moving east for an assistant’s job at Miami-Dade Junior College.

After four years in talent-rich south Florida, Polk took his first head coaching job at Georgia Southern, which was transitioning to Division I.

In 35 years as a college head coach at Georgia Southern, MSU and Georgia, Polk amassed a record of 1,373-702-2, guiding all three teams to the College World Series — including six CWS trips by MSU in two separate tenures there over a combined 29 seasons. His teams played in 23 NCAA regionals. He coached Team USA, the nation’s international team, for seven years, including Olympic Games in 1988 and 1992. He has been inducted into no fewer than six halls of fame.

Beyond the numbers

To understand Polk’s place in college baseball history, you have to go beyond the numbers and that story starts in Statesboro, Georgia, where a young first-time head coach would do on a small scale what he would accomplish on a far greater scale in the years to come.

With no staff, little money, even less fan support and terrible facilities, Polk poured himself into the new job, working endless hours, building a program from scratch.

The first year, the Eagles posted a respectable 31-19 record. Remarkably, in his second year, Georgia Southern rolled into the 1973 NCAA Tournament, winning the Starkville Regional to make it to the CWS.

Georgia Southern returned again to Starkville Regional the next year.

In four years at Georgia Southern, Polk’s teams posted a 155-64 record, but it was more than just winning games for Polk. It was about building a program, including facilities.

“We had to do something about the facilities,” Polk said. “I went to the home-builders association, civic clubs, everywhere I could think of trying to raise money.”

The funds Polk collected were placed in an account managed at the university president’s office.

“I went by there to see how much money we had, hoping we could put a roof on the dugout or something,” he said. “They told me that there had been a crisis and unfortunately the money had been spent on something else.”

Polk resigned at the season’s end but was out of a job only briefly.

Ron Fraser, who would become a legend at the University of Miami, offered Polk a job as his assistant. Polk’s Georgia Southern team had beaten Fraser and the Hurricanes in the 1973 Starkville Regional.

Polk worked under Fraser that fall, but the landscape was beginning to shift.

MSU coach Jimmy Bragan left after the 1975 season to join the coaching staff for the Milwaukee Brewers.

No doubt influenced by Polk’s success at the two Starkville regionals, MSU offered Polk the job.

In the meantime, Fraser was considering a front office job with the Chicago White Sox. The Miami Athletic Director told Polk the job was his if Fraser left.

Fraser decided to stay at Miami, where he became a legend. Polk headed to Starkville.

“If Fraser goes to the White Sox, none of this happens,” Polk says.

From cows to condos

Today, Mississippi State plays its games at Polk-Dement Stadium Dudy Noble Field, broadly considered one of the nation’s finest college baseball facility, the result of a $60-million renovation/expansion completed in 2019.

Beyond the left field fence, towers the Left Field Lofts — 12 two-bedroom apartments with balconies overlooking the field.

When Ron Polk arrived at MSU near the end of 1975, he saw something different at that location.

“Cows,” he said. “Everything beyond the fences was part of the university’s farm.”

Even so, it was in baseball that MSU had carved out a niche for itself in a sport long neglected by the Southeastern Conference.

As a small school with a small budget in a big conference, Mississippi State always played catch-up in most sports. Not so in baseball. The Bulldogs built what was then considered a solid fan base under previous coaches, including Dudy Noble and Paul Gregory. Its facilities were as good, if not a little better than the other SEC schools.

But Polk had far more ambitious plans.

“I just couldn’t figure out why the SEC wasn’t a baseball conference.” Polk said. “You’ve got the weather. You’ve got Florida, Georgia. In football, it’s Alabama. In basketball, it’s Kentucky, Baseball was just an afterthought. I always wondered why. Everything is here.”

Polk set out to change that.

“When I got here, I was the only baseball coach in the conference who didn’t have another job in the athletic department,” Polk said. “So there was a commitment.”

Everything else, it seemed, was up to Polk.

As he had at Georgia Southern, Polk quietly began stringing together winning seasons. Soon, fans were backing their cars and pickups along the left field fence. Goodbye cows.

In 1979, Polk took the first of his six Bulldog teams to the College World Series. Baseball was big-time at MSU — and others were watching.

Polk raised money for additions and renovations, constantly improving the facilities and watching his teams break attendance records along the way.

“The SEC is the dominant conference in baseball now and a lot of that is because of the success we had,” he said. “When we got a tarp, everybody had to get a tarp. When we got lights, everybody got lights. People watched what we were doing and they started thinking, ‘Maybe we can start making money in baseball.’”

From the time Polk arrived at MSU, it’s been the rest of the conference that has been playing catch-up.

“I think the best way to describe it is that Ron Polk awakened a sleeping giant,” said MSU Athletics Director John Cohen, one of Polk’s former Bulldog players. “The SEC is pretty good in everything, but when it came to baseball, it was kind of a hobby in the league. Coach Polk made baseball relevant here and he made it relevant at Mississippi State, he made it relevant for everybody else.”

In 1997, after leading MSU to 15 NCAA regionals and five College World Series appearances in 22 seasons, Polk retired, albeit briefly.

“I was just tired, overworked, getting into the office early in the morning and working until 11, 12 at night, doing what it took to build the program and fighting the NCAA tooth and nail,” Polk said.

Two years later, he was coaxed out of retirement to become baseball coach at Georgia. As he has at Georgia Southern 28 years earlier, Polk had Georgia in the College World Series in his second season (2001).

Baseball player Brad Cumbest talks with Ron Polk

When Pat McMahon, Polk’s assistant at MSU, resigned as the Bulldog coach to take the job at Florida, Polk again returned to State in 2002, picking up five more NCAA regional appearances and his sixth and final berth in the College World Series (2007) before retiring again in 2008.

His departure did not go well, leading to a 12-year estrangement caused when MSU chose Cohen rather than Tommy Raffo, Polk’s hand-picked choice as his successor.

For the next 12 years, Polk served as an unpaid assistant under another former player, Brian Shoop, at Alabama-Birmingham and coached in Cape Cope.

In 2020, when Shoop retired and Polk freed of his commitment to his former player, Cohen announced that Polk would return “home” to MSU as a special assistant to the AD.

“I just felt like it was important to get Coach Polk back in the Athletics Department,” Cohen said. “There’s no question what he means to the community and our athletic department.”

The Promised Land

Because of his coaching commitment in the Cape Cod League, Polk didn’t attend MSU’s first four games in the 2021 College World Series. He arrived in Omaha when MSU advanced to the best-of-three finals against Vanderbilt.

For the first two games, Polk was tucked into a seat behind the Bulldogs’ dugout.

But when he arrived for the deciding Game 3, Polk was ushered to the President’s Suite and a seat providing clear sight lines for the ESPN cameras, who wanted to be sure to capture Polk’s reaction as Mississippi State claimed the elusive national championship.

Six times as the Bulldogs coach, Polk had reached the CWS, the pinnacle of College baseball without reaching The Promised Land, a championship.

On June 30, as MSU ran away with a 9-0 win to claim the university’s first ever team championship, the ESPN cameras captured Polk’s reaction.

ESPN knew a first cause when it saw one, too.

STORY BY SLIM SMITH

PHOTOS BY RORY DOYLE